20 Apr 2016

Suppose you’re in the derivatives business. You are interested in making a

market on some events; say, whether or not your friend Jay will win tomorrow

night’s poker game, or that the winning pot will be at least USD 100. Let’s

examine some rules about how you should do business if you want this venture to

succeed.

What do I mean by ‘make a market’? I mean that you will be willing to buy and

sell units of a particular security that will be redeemable from the seller at

some particular value after tomorrow’s poker game has ended (you will be making

a simple prediction market, in other words). You can make bid offers to buy

securities at some price, and ask offers to sell securities at some price.

To keep things simple let’s say you’re doing this gratis; society rewards you

extrinsically for facilitating the market - your friends will give you free

pizza at the game, maybe - so you won’t levy any transaction fees for making

trades. Also scarcity isn’t a huge issue, so you’re willing to buy or sell any

finite number of securities.

Consider the possible outcomes of the game (one and only one of which must

occur):

- (A) Jay wins and the pot is at least USD 100.

- (B) Jay wins and the pot is less than USD 100.

- (C) Jay loses and the pot is at least USD 100.

- (D) Jay loses and the pot is less than USD 100.

The securities you are making a market on pay USD 1 if an event occurs, and USD

0 otherwise. So: if I buy 5 securities on outcome \(A\) from you, and outcome

\(A\) occurs, I’ll be able to go to you and redeem my securities for a total of

USD 5. Alternatively, if I sell you 5 securities on outcome \(A\), and outcome

\(A\) occurs, you’ll be able to come to me and redeem your securities for a

total of USD 5.

Consider what that implies: as a market maker, you face the prospect of making

hefty payments to customers who redeem valuable securities. For example,

imagine the situation where you charge USD 0.50 for a security on outcome

\(A\), but outcome \(A\) is almost certain to occur in some sense (Jay is a

beast when it comes to poker and a lot of high rollers are playing); if your

customers exclusively load up on 100 cheap securities on outcome \(A\), and

outcome \(A\) occurs, then you stand to owe them a total payment of USD 100

against the USD 50 that they have paid for the securities. You thus have a

heavy incentive to price your securities as accurately as possible - where

‘accurate’ means to minimize your expected loss.

It may always be the case, however, that it is difficult to price your

securities accurately. For example, if some customer has more information than

you (say, she privately knows that Jay is unusually bad at poker) then she

potentially stands to profit from holding said information in lieu of your

ignorance on the matter (and that of your prices). Such is life for a market

maker. But there are particular prices you could offer - independent of any

participant’s private information - that are plainly stupid or ruinous for you

(a set of prices like this is sometimes called a Dutch

book). Consider selling securities

on outcome \(A\) for the price of USD -1; then anyone who buys one of these

securities not only stands to redeem USD 1 in the event outcome \(A\) occurs,

but also gains USD 1 simply from the act of buying the security in the first

place.

Setting a negative price like this is irrational on your part; customers will

realize an arbitrage opportunity on securities for outcome \(A\) and will

happily buy as many as they can get their hands on, to your ruin. In other

words - and to nobody’s surprise - by setting a negative price, you can be

made a sure loser in the market.

There are other prices you should avoid setting as well, if you want to avoid

arbitrage opportunities like these. For starters:

- For any outcome \(E\), you must set the price of a security on \(E\) to be at

least USD 0.

- For any certain outcome \(E\), you must set the price of a security on \(E\) to

be exactly USD 1.

The first condition rules out negative prices, and the second ensures that your

books balance when it comes time to settle payment for securities on a certain

event.

What’s more, the price that you set on any given security doesn’t exist in

isolation. Given the outcomes \(A\), \(B\), \(C\), and \(D\) listed previously, at

least one must occur. So as per the second rule, the price of a synthetic

derivative on the outcome “Jay wins or loses, and the pot is any value” must be

set to USD 1. This places constraints on the prices that you can set for

individual securities. It suffices that:

- For any countable set of mutually exclusive outcomes \(E_{1}, E_{2}, \ldots\),

you must set the price of the security on outcome “\(E_{1}\) or \(E_{2}\) or..”

to exactly the sum of the prices of the individual outcomes.

This eliminates the possibility that your customers will make you a certain

loser by buying elaborate combinations of securities on different outcomes.

There are other rules that your prices must obey as well, but they fall out as

corollaries of these three. If you broke any of them you’d also be breaking

one of these.

It turns out that you cannot be made a sure loser if, and only if, your prices

obey these three rules. That is:

- If your prices follow these rules, then you will offer customers no arbitrage

opportunities.

- Any market absent of arbitrage opportunities must have prices that conform

to these rules.

These prices are called coherent, and absence of coherence implies the

existence of arbitrage opportunities for your customers.

But Why Male Models

The trick, of course, is that these prices correspond to probabilities, and

the rules for avoiding arbitrage correspond to the standard Kolmogorov

axioms of probability

theory.

The consequence is that if your description of uncertain phenomena does not

involve probability theory, or does not behave exactly like probability theory,

then it is an incoherent representation of information you have about those

phenomena.

As a result, probability theory should be your tool of choice when it comes

to describing uncertain phenomena. Granted you may not have to worry about

market making in return for pizza, but you’d like to be assured that there are

no structural problems with your description.

This is a summary of the development of probability presented in Jay Kadane’s

brilliant Principles of Uncertainty. The

original argument was developed by de Finetti and Savage in the mid-20th

century.

Kadane’s book makes for an exceptional read, and it’s free to boot. I

recommend checking it out if it has flown under your radar.

An interesting characteristic of this development of probability is that there

is no way to guarantee the nonexistence of arbitrage opportunities for a

countably infinite number of purchased securities. That is: if you’re a market

maker, you could be made a sure loser in the market when it came time for you

to settle a countably infinite number of redemption claims. The quirk here is

that you could also be made a sure winner as well; whether you win or lose with

certainty depends on the order in which the claims are settled! (Fortunately

this doesn’t tend to be an issue in practice.)

Thanks to Fredrik Olsen for reviewing a draft of this post.

References

07 Apr 2016

I’ve updated my old flat-mcmc library

for ensemble sampling in Haskell and have pushed out a v1.0.0 release.

History

I wrote flat-mcmc in 2012, and it was the first serious-ish size project I

attempted in Haskell. It’s an implementation of Goodman & Weare’s affine

invariant ensemble

sampler, a Monte Carlo

algorithm that works by running a Markov chain over an ensemble of particles.

It’s easy to get started with (there are no tuning parameters, etc.) and

is sufficiently robust for a lot of purposes. The algorithm became somewhat

famous in the astrostatistics community, where some of its members implemented

it via the very nice and polished Python library,

emcee.

The library has become my second-most starred repo on Github, with a whopping

10 stars as of this writing (the Haskell MCMC community is pretty niche, bro).

Lately someone emailed me and asked if I wouldn’t mind pushing it to Stackage,

so I figured it was due for an update and gave it a little modernizing along

the way.

I’m currently on sabbatical and am traveling through Vietnam; I started the

rewrite in Hanoi and finished it in Saigon, so it was a kind of nice side

project to do while sipping coffees and the like during downtime.

What Is It

I wrote a little summary of the library in 2012, which you can still find

tucked away on my personal site. Check that out

if you’d like a description of the algorithm and why you might want to use it.

Since I wrote the initial version my astrostatistics-inclined friends David

Huijser and Brendon Brewer wrote a paper

about some limitations they discovered when using this algorithm in

high-dimensional settings. So caveat emptor, buyer beware and all that.

In general this is an extremely easy-to-use algorithm that will probably get

you decent samples from arbitrary targets without tedious tuning/fiddling.

What’s New

I’ve updated and standardized the API in line with my other MCMC projects

huddled around the declarative library. That means

that, like the others, there are two primary ways to use the library: via an

mcmc function that will print a trace to stdout, or a flat transition

operator that can be used to work with chains in memory.

Regrettably you can’t use the flat transition operator with others in the

declarative ecosystem as it operates over ensembles, whereas the others are

single-particle algorithms.

The README over at the Github repo

contains a brief usage example. If there’s some feature you’d like to see or

documentation/examples you could stand to have added then don’t hestitate to

ping me and I’ll be happy to whip something up.

In the meantime I’ve pushed a new version to

Hackage and added the library

to Stackage, so it should show up in an LTS

release soon enough.

Cheers!

16 Feb 2016

Applicative functors are useful

for encoding context-free effects. This typically gets put to work around

things like parsing

or validation,

but if you have a statistical bent then an applicative structure will be

familiar to you as an encoder of independence.

In this article I’ll give a whirlwind tour of probability monads and algebraic

freeness, and demonstrate that applicative functors can be used to represent

independence between probability distributions in a way that can be verified

statically.

I’ll use the following preamble for the code in the rest of this article.

You’ll need the free and

mwc-probability

libraries if you’re following along at home:

{-# LANGUAGE DeriveFunctor #-}

{-# LANGUAGE LambdaCase #-}

import Control.Applicative

import Control.Applicative.Free

import Control.Monad

import Control.Monad.Free

import Control.Monad.Primitive

import System.Random.MWC.Probability (Prob)

import qualified System.Random.MWC.Probability as MWC

Probability Distributions and Algebraic Freeness

Many functional programmers (though fewer statisticians) know that probability

has a monadic structure. This

can be expressed in multiple ways; the discrete probability distribution type

found in the

PFP framework,

the sampling function representation used in the

lambda-naught paper (and

implemented here, for example),

and even an obscure measure-based

representation first described by Ramsey and Pfeffer, which doesn’t have a ton

of practical use.

The monadic structure allows one to sequence distributions together. That is:

if some distribution ‘foo’ has a parameter which itself has the probability

distribution ‘bar’ attached to it, the compound distribution can be expressed

by the monadic expression ‘bar »= foo’.

At a larger scale, monadic programs like this correspond exactly to what you’d

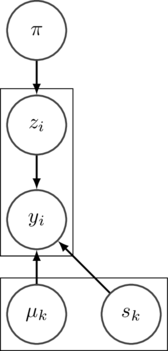

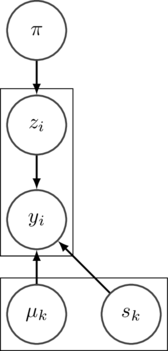

typically see in a run-of-the-mill visualization of a probabilistic model:

In this classical kind of visualization the nodes represent probability

distributions and the arrows describe the dependence structure. Translating it

to a monadic program is mechanical: the nodes become monadic expressions and

the arrows become binds. You’ll see a simple example in this article shortly.

The monadic structure of probability implies that it also has a functorial

structure. Mapping a function over some probability distrubution will

transform its support while leaving its probability density structure invariant

in some sense. If the function ‘uniform’ defines a uniform probability

distribution over the interval (0, 1), then the function ‘fmap (+ 1) uniform’

will define a probability distribution over the interval (1, 2).

I’ll come back to probability shortly, but the point is that probability

distributions have a clear and well-defined algebraic structure in terms of

things like functors and monads.

Recently free objects have become fashionable in functional programming. I

won’t talk about it in detail here, but algebraic ‘freeness’ corresponds to a

certain preservation of structure, and exploiting this kind of preserved

structure is a useful technique for writing and interpreting programs.

Gabriel Gonzalez famously wrote about freeness in an oft-cited

article

about free monads, John De Goes wrote a compelling piece on the topic in the

excellent A Modern Architecture for Functional

Programming, and just today I noticed

that Chris Stucchio had published an article on using Free Boolean

Algebras for implementing

a kind of constraint DSL. The last article included the following quote, which

IMO sums up much of the raison d’être to exploit freeness in your day-to-day

work:

.. if you find yourself re-implementing the same algebraic structure over and over, it might be worth asking yourself if a free version of that algebraic structure exists. If so, you might save yourself a lot of work by using that.

If a free version of some structure exists, then it embodies the ‘essence’ of

that structure, and you can encode specific instances of it by just layering

the required functionality over the free object itself.

A Type for Probabilistic Models

Back to probability. Since probability distributions are monads, we can use a

free monad to encode them in a structure-preserving way. Here I’ll define a

simple probability base functor for which each constructor is a particular

‘named’ probability distribution:

data ProbF r =

BetaF Double Double (Double -> r)

| BernoulliF Double (Bool -> r)

deriving Functor

type Model = Free ProbF

Here we’ll only work with two simple named distributions - the beta and the

Bernoulli - but the sky is the limit.

The ‘Model’ type wraps up this probability base functor in the free monad,

‘Free’. In this sense a ‘Model’ can be viewed as a program parameterized by

the underlying probabilistic instruction set defined by ‘ProbF’ (a technique I

described

recently).

Expressions with the type ‘Model’ are terms in an embedded language. We can

create some user-friendly ones for our beta-bernoulli language like so:

beta :: Double -> Double -> Model Double

beta a b = liftF (BetaF a b id)

bernoulli :: Double -> Model Bool

bernoulli p = liftF (BernoulliF p id)

Those primitive terms can then be used to construct expressions.

The beta and Bernoulli distributions enjoy an algebraic property called

conjugacy that ensures

(amongst other things) that the compound distribution formed by combining the

two of them is analytically

tractable. Here’s a

parameterized coin constructed by doing just that:

coin :: Double -> Double -> Model Bool

coin a b = beta a b >>= bernoulli

By tweaking the parameters ‘a’ and ‘b’ we can bias the coin in particular ways,

making it more or less likely to observe a head when it’s inspected.

A simple evaluator for the language goes like this:

eval :: PrimMonad m => Model a -> Prob m a

eval = iterM $ \case

BetaF a b k -> MWC.beta a b >>= k

BernoulliF p k -> MWC.bernoulli p >>= k

‘iterM’ is a monadic, catamorphism-like recursion

scheme

that can be used to succinctly consume a ‘Model’. Here I’m using it to

propagate uncertainty through the model by sampling from it ancestrally in a

top-down manner. The ‘MWC.beta’ and ‘MWC.bernoulli’ functions are sampling

functions from the mwc-probability library, and the resulting type ‘Prob m a’

is a simple probability monad type based on sampling functions.

To actually sample from the resulting ‘Prob’ type we can use the system’s PRNG

for randomness. Here are some simple coin tosses with various biases as an

example; you can mentally substitute ‘Head’ for ‘True’ if you’d like:

> gen <- MWC.createSystemRandom

> replicateM 10 $ MWC.sample (eval (coin 1 1)) gen

[False,True,False,False,False,False,False,True,False,False]

> replicateM 10 $ MWC.sample (eval (coin 1 8)) gen

[False,False,False,False,False,False,False,False,False,False]

> replicateM 10 $ MWC.sample (eval (coin 8 1)) gen

[True,True,True,False,True,True,True,True,True,True]

As a side note: encoding probability distributions in this way means that the

other ‘forms’ of probability monad described previously happen to fall out

naturally in the form of specific interpreters over the free monad itself. A

measure-based probability monad could be achieved by using a different ‘eval’

function; the important monadic structure is already preserved ‘for free’:

measureEval :: Model a -> Measure a

measureEval = iterM $ \case

BetaF a b k -> Measurable.beta a b >>= k

BernoulliF p k -> Measurable.bernoulli p >>= k

Independence and Applicativeness

So that’s all cool stuff. But in some cases the monadic structure is more than

what we actually require. Consider flipping two coins and then returning them

in a pair, for example:

flips :: Model (Bool, Bool)

flips = do

c0 <- coin 1 8

c1 <- coin 8 1

return (c0, c1)

These coins are independent - they don’t affect each other whatsoever and enjoy

the probabilistic/statistical

property that

formalizes that relationship. But the monadic program above doesn’t actually

capture this independence in any sense; desugared, the program actually

proceeds like this:

flips =

coin 1 8 >>= \c0 ->

coin 8 1 >>= \c1 ->

return (c0, c1)

On the right side of any monadic bind we just have a black box - an opaque

function that can’t be examined statically. Each monadic expression binds its

result to the rest of the program, and we - programming ‘at the surface’ -

can’t look at it without going ahead and evaluating it. In particular we can’t

guarantee that the coins are truly independent - it’s just a mental invariant

that can’t be transferred to an interpreter.

But this is the well-known motivation for applicative functors, so we can do a

little better here by exploiting them. Applicatives are strictly less

powerful than monads, so they let us write a probabilistic program that can

guarantee the independence of expressions.

Let’s bring in the free applicative, ‘Ap’. I’ll define a type called ‘Sample’

by layering ‘Ap’ over our existing ‘Model’ type:

So an expression with type ‘Sample’ is a free applicative over the ‘Model’ base

functor. I chose the namesake because typically we talk about samples that are

independent and identically-distributed draws from some probability

distribution, though we could use ‘Ap’ to collect samples that are

independently-but-not-identically distributed as well.

To use our existing embedded language terms with the free applicative, we can

create the following helper function as an alias for ‘liftAp’ from

‘Control.Applicative.Free’:

independent :: f a -> Ap f a

independent = liftAp

With that in hand, we can write programs that statically encode independence.

Here are the two coin flips from earlier (and if you’re applicative-savvy I’ll

avoid using ‘liftA2’ here for clarity):

flips :: Sample (Bool, Bool)

flips = (,) <$> independent (coin 1 8) <*> independent (coin 8 1)

The applicative structure enforces exactly what we want: that no part of the

effectful computation can depend on a previous part of the effectful

computation. Or in probability-speak: that the distributions involved do not

depend on each other in any way (they would be captured by the plate notation

in the visualization shown previously).

To wrap up, we can reuse our previous evaluation function to interpret a

‘Sample’ into a value with the ‘Prob’ type:

evalIndependent :: PrimMonad m => Sample a -> Prob m a

evalIndependent = runAp eval

And from here it can just be evaluated as before:

> MWC.sample (evalIndependent flips) gen

(False,True)

Conclusion

That applicativeness embodies context-freeness seems to be well-known when it

comes to parsing, but its relation to independence in probability theory seems

less so.

Why might this be useful, you ask? Because preserving structure is mandatory

for performing inference on probabilistic programs, and it’s safe to bet that

the more structure you can capture, the easier that job will be.

In particular, algorithms for sampling from independent distributions tend to

be simpler and more efficient than those useful for sampling from dependent

distributions (where you might want something like Hamiltonian Monte

Carlo or

NUTS). Identifying independent components

of a probabilistic program statically could thus conceptually simplify the task

of sampling from some conditioned programs quite a bit - and

that

matters.

Enjoy! I’ve dumped the code from this article into a

gist.