09 Feb 2016

In Practical Recursion

Schemes

I talked about recursion schemes, describing them as elegant and useful

patterns for expressing general computation. In that article I introduced a

number of things relevant to working with the

recursion-schemes

package in Haskell.

In particular, I went over:

- factoring the recursion out of recursive types using base functors and a

fixed-point wrapper

- the ‘Foldable’ and ‘Unfoldable’ typeclasses corresponding to recursive and

corecursive data types, plus their ‘project’ and ‘embed’ functions

respectively

- the ‘Base’ type family that maps recursive types to their base functors

- some of the most common and useful recursion schemes: cata, ana, para,

and hylo.

In A Tour of Some Useful Recursive

Types

I went into further detail on ‘Fix’, ‘Free’, and ‘Cofree’ - three higher-kinded

recursive types that are useful for encoding programs defined by some

underlying instruction set.

I’ve also posted a couple of minor notes - I described the apo scheme in

Sorting Slower With Style (as well as how to use

recursion-schemes with regular Haskell lists) and chatted about monadic

versions of the various schemes in Monadic Recursion

Schemes.

Here I want to clue up this whole recursion series by briefly talking about two

other recursion schemes - histo and futu - that work by looking at the past

or future of the recursion respectively.

Here’s a little preamble for the examples to come:

{-# LANGUAGE LambdaCase #-}

{-# LANGUAGE TypeFamilies #-}

import Control.Comonad.Cofree

import Control.Monad.Free

import Data.Functor.Foldable

Histomorphisms

Histomorphisms are terrifically simple - they just give you access to arbitrary

previously-computed values of the recursion at any given point (its history,

hence the namesake). They’re perfectly suited to dynamic programming problems,

or anything where you might need to re-use intermediate computations later.

Histo needs a data structure to store the history of the recursion in. The

the natural choice there is ‘Cofree’, which allows one to annotate recursive

types with arbitrary metadata. Brian McKenna wrote a great

article on making

practical use of these kind of annotations awhile back.

But yeah, histomorphisms are very easy to use. Check out the following

function that returns all the odd-indexed elements of a list:

oddIndices :: [a] -> [a]

oddIndices = histo $ \case

Nil -> []

Cons h (_ :< Nil) -> [h]

Cons h (_ :< Cons _ (t :< _)) -> h:t

The value to the left of a ‘:<’ constructor is an annotation provided by

‘Cofree’, and the value to right is the (similarly annotated) next step of the

recursion. The annotations at any point are the previously computed values of

the recursion corresponding to that point.

So in the case above, we’re just grabbing some elements from the input list and

ignoring others. The algebra is saying:

- if the input list is empty, return an empty list

- if the input list has only one element, return that one-element list

- if the input list has at least two elements, return the list built by

cons-ing the first element together with the list computed two steps ago

The list computed two steps ago is available as the annotation on the

constructor two steps down - I’ve matched it as ‘t’ in the last line of the

above example. Like cata, histo works from the bottom-up.

A function that computes even indices is similar:

evenIndices :: [a] -> [a]

evenIndices = histo $ \case

Nil -> []

Cons _ (_ :< Nil) -> []

Cons _ (_ :< Cons h (t :< _)) -> h:t

Futumorphisms

Like histomorphisms, futumorphisms are also simple. They give you access to

a particular computed part of the recursion at any given point.

However I’ll concede that the perceived simplicity probably comes with

experience, and there is likely some conceptual weirdness to be found here.

Just as histo gives you access to previously-computed values, futu gives

you access to values that the recursion will compute in the future.

So yeah, that sounds crazy. But the reality is more mundane, if you’re

familiar with the underlying concepts.

For histo, the recursion proceeds from the bottom up. At each point, the

part of the recursive type you’re working with is annotated with the value of

the recursion at that point (using ‘Cofree’), so you can always just reach back

and grab it for use in the present.

With futu, the recursion proceeds from the top down. At each point, you

construct an expression that can make use of a value to be supplied later.

When the value does become available, you can use it to evaluate the

expression.

A histomorphism makes use of ‘Cofree’ to do its annotation, so it should be no

surprise that a futumorphism uses the dual structure - ‘Free’ - to create its

expressions. The well-known ‘free monad’ is tremendously

useful

for working with small embedded languages. I also wrote about ‘Free’ in the

same article mentioned previously, so I’ll link it

again

in case you want to refer to it.

As an example, we’ll use futu to implement the same two functions that we did

for histo. First, the function that grabs all odd-indexed elements:

oddIndicesF :: [a] -> [a]

oddIndicesF = futu coalg where

coalg list = case project list of

Nil -> Nil

Cons x s -> Cons x $ do

return $ case project s of

Nil -> s

Cons _ t -> t

The coalgebra is saying the following:

- if the input list is empty, return an empty list

- if the input list has at least one element, construct an expression that

will use a value to be supplied later.

- if the supplied value turns out to be empty, return the one-element list.

- if the supplied value turns out to have at least one more element, return the

list constructed by skipping it, and using the value from another step in

the future.

You can write that function more concisely, and indeed

HLint will complain at you for

writing it as I’ve done above. But I think this one makes it clear what parts

are happening based on values to be supplied in the future. Namely, anything

that occurs after ‘do’.

It’s kind of cool - you Enter The Monad™ and can suddenly work with values that

don’t exist yet, while treating them as if they do.

Here’s futu-implemented ‘evenIndices’ for good measure:

evenIndicesF :: [a] -> [a]

evenIndicesF = futu coalg where

coalg list = case project list of

Nil -> Nil

Cons _ s -> case project s of

Nil -> Nil

Cons h t -> Cons h $ return t

Sort of a neat feature is that ‘Free’ part of the coalgebra can be written

a little cleaner if you have ‘Free’-encoded embedded language terms floating

around. Here are a couple of such terms, plus a ‘twiddle’ function that uses

them to permute elements of an input list as they’re encountered:

nil :: Free (Prim [a]) b

nil = liftF Nil

cons :: a -> b -> Free (Prim [a]) b

cons h t = liftF (Cons h t)

twiddle :: [a] -> [a]

twiddle = futu coalg where

coalg r = case project r of

Nil -> Nil

Cons x l -> case project l of

Nil -> Cons x nil

Cons h t -> Cons h $ cons x t

If you’ve been looking to twiddle elements of a recursive type then you’ve

found a classy way to do it:

> take 20 $ twiddle [1..]

[2,1,4,3,6,5,8,7,10,9,12,11,14,13,16,15,18,17,20,19]

Enjoy! You can find the code from this article in this

gist.

20 Jan 2016

I have another few posts that I’d like to write before cluing up the

whole recursion schemes kick I’ve been

on. The first is a simple note about monadic versions of the schemes

introduced thus far.

In practice you often want to deal with effectful versions of something like

cata. Take a very simple embedded language, for example (“Hutton’s Razor”,

with variables):

{-# LANGUAGE DeriveFunctor #-}

{-# LANGUAGE DeriveFoldable #-}

{-# LANGUAGE DeriveTraversable #-}

{-# LANGUAGE LambdaCase #-}

import Control.Monad ((<=<), liftM2)

import Control.Monad.Trans.Class (lift)

import Control.Monad.Trans.Reader (ReaderT, ask, runReaderT)

import Data.Functor.Foldable hiding (Foldable, Unfoldable)

import qualified Data.Functor.Foldable as RS (Foldable, Unfoldable)

import Data.Map.Strict (Map)

import qualified Data.Map.Strict as Map

data ExprF r =

VarF String

| LitF Int

| AddF r r

deriving (Show, Functor, Foldable, Traversable)

type Expr = Fix ExprF

var :: String -> Expr

var = Fix . VarF

lit :: Int -> Expr

lit = Fix . LitF

add :: Expr -> Expr -> Expr

add a b = Fix (AddF a b)

(Note: Make sure you import ‘Data.Functor.Foldable.Foldable’ with a

qualifier because GHC’s ‘DeriveFoldable’ pragma will become confused if there

are multiple ‘Foldables’ in scope.)

Take proper error handling over an expression of type ‘Expr’ as an example; at

present we’d have to write an ‘eval’ function as something like

eval :: Expr -> Int

eval = cata $ \case

LitF j -> j

AddF i j -> i + j

VarF _ -> error "free variable in expression"

This is a bit of a non-starter in a serious or production implementation, where

errors are typically handled using a higher-kinded type like ‘Maybe’ or

‘Either’ instead of by just blowing up the program on the spot. If we hit an

unbound variable during evaluation, we’d be better suited to return an error

value that can be dealt with in a more appropriate place.

Look at the algebra used in ‘eval’; what would be useful is something like

monadicAlgebra = \case

LitF j -> return j

AddF i j -> return (i + j)

VarF v -> Left (FreeVar v)

data Error =

FreeVar String

deriving Show

This won’t fly with cata as-is, and recursion-schemes doesn’t appear to

include any support for monadic variants out of the box. But we can produce a

monadic cata - as well as monadic versions of the other schemes I’ve talked

about to date - without a lot of trouble.

To begin, I’ll stoop to a level I haven’t yet descended to and include a

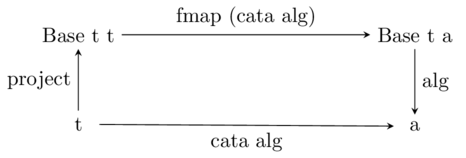

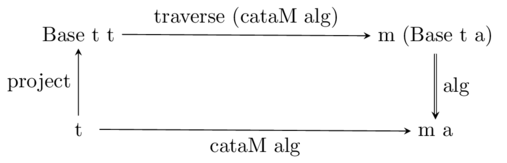

commutative diagram that defines a catamorphism:

To read it, start in the bottom left corner and work your way to the bottom

right. You can see that we can go from a value of type ‘t’ to one of type ‘a’

by either applying ‘cata alg’ directly, or by composing a bunch of other

functions together.

If we’re trying to define cata, we’ll obviously want to do it in terms

of the compositions:

cata:: (RS.Foldable t) => (Base t a -> a) -> t -> a

cata alg = alg . fmap (cata alg) . project

Note that in practice it’s typically more

efficient

to write recursive functions using a non-recursive wrapper, like so:

cata:: (RS.Foldable t) => (Base t a -> a) -> t -> a

cata alg = c where c = alg . fmap c . project

This ensures that the function can be inlined. Indeed, this is the version

that recursion-schemes uses internally.

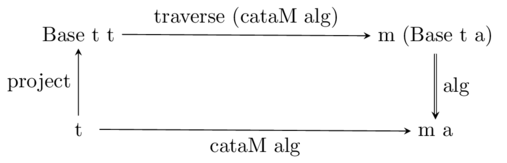

To get to a monadic version we need to support a monadic algebra - that is, a

function with type ‘Base t a -> m a’ for appropriate ‘t’. To translate the

commutative diagram, we need to replace ‘fmap’ with ‘traverse’ (requiring a

‘Traversable’ instance) and the final composition with monadic (or Kleisli)

composition:

The resulting function can be read straight off the diagram, modulo additional

constraints on type variables. I’ll go ahead and write it directly in the

inline-friendly way:

cataM

:: (Monad m, Traversable (Base t), RS.Foldable t)

=> (Base t a -> m a) -> t -> m a

cataM alg = c where

c = alg <=< traverse c . project

Going back to the previous example, we can now define a proper ‘eval’ as

follows:

eval :: Expr -> Either Error Int

eval = cataM $ \case

LitF j -> return j

AddF i j -> return (i + j)

VarF v -> Left (FreeVar v)

This will of course work for any monad. A common pattern on an ‘eval’ function

is to additionally slap on a ‘ReaderT’ layer to supply an environment, for

example:

eval :: Expr -> ReaderT (Map String Int) (Either Error) Int

eval = cataM $ \case

LitF j -> return j

AddF i j -> return (i + j)

VarF v -> do

env <- ask

case Map.lookup v env of

Nothing -> lift (Left (FreeVar v))

Just j -> return j

And just an example of how that works:

> let open = add (var "x") (var "y")

> runReaderT (eval open) (Map.singleton "x" 1)

Left (FreeVar "y")

> runReaderT (eval open) (Map.fromList [("x", 1), ("y", 5)])

Right 6

You can follow the same formula to create the other monadic recursion schemes.

Here’s monadic ana:

anaM

:: (Monad m, Traversable (Base t), RS.Unfoldable t)

=> (a -> m (Base t a)) -> a -> m t

anaM coalg = a where

a = (return . embed) <=< traverse a <=< coalg

and monadic para, apo, and hylo follow in much the same way:

paraM

:: (Monad m, Traversable (Base t), RS.Foldable t)

=> (Base t (t, a) -> m a) -> t -> m a

paraM alg = p where

p = alg <=< traverse f . project

f t = liftM2 (,) (return t) (p t)

apoM

:: (Monad m, Traversable (Base t), RS.Unfoldable t)

=> (a -> m (Base t (Either t a))) -> a -> m t

apoM coalg = a where

a = (return . embed) <=< traverse f <=< coalg

f = either return a

hyloM

:: (Monad m, Traversable t)

=> (t b -> m b) -> (a -> m (t a)) -> a -> m b

hyloM alg coalg = h

where h = alg <=< traverse h <=< coalg

These are straightforward extensions from the basic schemes. A good exercise

is to try putting together the commutative diagrams corresponding to each

scheme yourself, and then use them to derive the monadic versions. That’s

pretty fun to do for para and apo in particular.

If you’re using these monadic versions in your own project, you may want to

drop them into a module like ‘Data.Functor.Foldable.Extended’ as recommended

by

my colleague Jasper Van der Jeugt. Additionally, there is an old

issue floating around on

the recursion-schemes repo that proposes adding them to the library itself.

So maybe they’ll turn up in there eventually.

19 Jan 2016

I previously wrote about implementing merge sort using

recursion schemes. By using a hylomorphism we

could express the algorithm concisely and true to its high-level description.

Insertion sort can be

implemented in a similar way - this time by putting one recursion scheme inside

of another.

Read on for details.

Apomorphisms

These guys don’t seem to get a lot of love in the recursion scheme tutorial du

jour, probably because they might be the first scheme you encounter that looks

truly weird on first glance. But apo is really not bad at all - I’d go so

far as to call apomorphisms straightforward and practical.

So: if you remember your elementary recursion schemes, you can say that apo

is to ana as para is to cata. A paramorphism gives you access to a value

of the original input type at every point of the recursion; an apomorphism lets

you terminate using a value of the original input type at any point of the

recursion.

This is pretty useful - often when traversing some structure you just want to

bail out and return some value on the spot, rather than continuing on recursing

needlessly.

A good introduction is the toy ‘mapHead’ function that maps some other function

over the head of a list and leaves the rest of it unchanged. Let’s first rig

up a hand-rolled list type to illustrate it on:

{-# LANGUAGE DeriveFunctor #-}

{-# LANGUAGE TypeFamilies #-}

import Data.Functor.Foldable

data ListF a r =

ConsF a r

| NilF

deriving (Show, Functor)

type List a = Fix (ListF a)

fromList :: [a] -> List a

fromList = ana coalg . project where

coalg Nil = NilF

coalg (Cons h t) = ConsF h t

(I’ll come back to the implementation of ‘fromList’ later, but for now you can

see it’s implemented via an anamorphism.)

Example One

Here’s ‘mapHead’ for our hand-rolled list type, implemented via apo:

mapHead :: (a -> a) -> List a -> List a

mapHead f = apo coalg . project where

coalg NilF = NilF

coalg (ConsF h t) = ConsF (f h) (Left t)

Before I talk you through it, here’s a trivial usage example:

> fromList [1..3]

Fix (ConsF 1 (Fix (ConsF 2 (Fix (ConsF 3 (Fix NilF))))))

> mapHead succ (fromList [1..3])

Fix (ConsF 2 (Fix (ConsF 2 (Fix (ConsF 3 (Fix NilF))))))

Now. Take a look at the coalgebra involved in writing ‘mapHead’. It has the

type ‘a -> Base t (Either t a)’, which for our hand-rolled list case simplifies

to ‘a -> ListF a (Either (List a) a)’.

Just as a reminder, you can check this in GHCi using the ‘:kind!’ command:

> :set -XRankNTypes

> :kind! forall a. a -> Base (List a) (Either (List a) a)

forall a. a -> Base (List a) (Either (List a) a) :: *

= a -> ListF a (Either (List a) a)

So, inside any base functor on the right hand side we’re going to be dealing

with some ‘Either’ values. The ‘Left’ branch indicates that we’re going to

terminate the recursion using whatever value we pass, whereas the ‘Right’

branch means we’ll continue recursing as per normal.

In the case of ‘mapHead’, the coalgebra is saying:

- deconstruct the list; if it has no elements just return an empty list

- if the list has at least one element, return the list constructed by

prepending ‘f h’ to the existing tail.

Here the ‘Left’ branch is used to terminate the recursion and just return the

existing tail on the spot.

Example Two

That was pretty easy, so let’s take it up a notch and implement list

concatenation:

cat :: List a -> List a -> List a

cat l0 l1 = apo coalg (project l0) where

coalg NilF = case project l1 of

NilF -> NilF

ConsF h t -> ConsF h (Left t)

coalg (ConsF x l) = case project l of

NilF -> ConsF x (Left l1)

ConsF h t -> ConsF x (Right (ConsF h t))

This one is slightly more involved, but the principles are almost entirely the

same. If both lists are empty we just return an empty list, and if the first

list has at most one element we return the list constructed by jamming the

second list onto it. The ‘Left’ branch again just terminates the recursion and

stops everything there.

If both lists are nonempty? Then we actually do some work and recurse, which

is what the ‘Right’ branch indicates.

So hopefully you can see there’s nothing too weird going on - the coalgebras

are really simple once you get used to the Either constructors floating around

in there.

Paramorphisms involve an algebra that gives you access to a value of the

original input type in a pair - a product of two values. Since apomorphisms

are their dual, it’s no surprise that you can give them a value of the original

input type using ‘Either’ - a sum of two values.

Insertion Sort

So yeah, my favourite example of an apomorphism is for implementing the ‘inner

loop’ of insertion sort, a famous worst-case \(O(n^2)\) comparison-based

sort. Granted that insertion sort itself is a bit of a toy algorithm, but the

pattern used to implement its internals is pretty interesting and more broadly

applicable.

This animation found on

Wikipedia

illustrates how insertion sort works:

We’ll actually be doing this thing in reverse - starting from the right-hand

side and scanning left - but here’s the inner loop that we’ll be concerned

with: if we’re looking at two elements that are out of sorted order, slide the

offending element to where it belongs by pushing it to the right until it hits

either a bigger element or the end of the list.

As an example, picture the following list:

[3, 1, 1, 2, 4, 3, 5, 1, 6, 2, 1]

The first two elements are out of sorted order, so we want to slide the 3

rightwards along the list until it bumps up against a larger element - here

that’s the 4.

The following function describes how to do that in general for our hand-rolled

list type:

coalg NilF = NilF

coalg (ConsF x l) = case project l of

NilF -> ConsF x (Left l)

ConsF h t

| x <= h -> ConsF x (Left l)

| otherwise -> ConsF h (Right (ConsF x t))

It says:

- deconstruct the list; if it has no elements just return an empty list

- if the list has only one element, or has at least two elements that are in

sorted order, terminate with the original list by passing the tail of the

list in the ‘Left’ branch

- if the list has at least two elements that are out of sorted order, swap

them and recurse using the ‘Right’ branch

And with that in place, we can use an apomorphism to put it to work:

knockback :: Ord a => List a -> List a

knockback = apo coalg . project where

coalg NilF = NilF

coalg (ConsF x l) = case project l of

NilF -> ConsF x (Left l)

ConsF h t

| x <= h -> ConsF x (Left l)

| otherwise -> ConsF h (Right (ConsF x t))

Check out how it works on our original list, slotting the leading 3 in front of

the 4 as required. I’ll use a regular list here for readability:

> let test = [3, 1, 1, 2, 4, 3, 5, 1, 6, 2, 1]

> knockbackL test

[1, 1, 2, 3, 4, 3, 5, 1, 6, 2, 1]

Now to implement insertion sort we just want to do this repeatedly like in the

animation above.

This isn’t something you’d likely notice at first glance, but check out the

type of ‘knockback . embed’:

> :t knockback . embed

knockback . embed :: Ord a => ListF a (List a) -> List a

That’s an algebra in the ‘ListF a’ base functor, so we can drop it into cata:

insertionSort :: Ord a => List a -> List a

insertionSort = cata (knockback . embed)

And voila, we have our sort.

If it’s not clear how the thing works, you can visualize the whole process as

working from the back of the list, knocking back unsorted elements and

recursing towards the front like so:

[]

[1]

[2, 1] -> [1, 2]

[6, 1, 2] -> [1, 2, 6]

[1, 1, 2, 6]

[5, 1, 1, 2, 6] -> [1, 1, 2, 5, 6]

[3, 1, 1, 2, 5, 6] -> [1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 6]

[4, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 6] -> [1, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

[2, 1, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] -> [1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

[1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

[1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

[3, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] -> [1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 4, 5, 6]

[1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 4, 5, 6]

Wrapping Up

And that’s it! If you’re unlucky you may be sorting asymptotically worse than

if you had used mergesort. But at least you’re doing it with style.

The ‘mapHead’ and ‘cat’ examples come from the unreadable Vene and

Uustalu paper that first

described apomorphisms. The insertion sort example comes from Tim Williams’s

excellent recursion schemes

talk.

As always, I’ve dumped the code for this article into a

gist.

Addendum: Using Regular Lists

You’ll note that the ‘fromList’ and ‘knockbackL’ functions above operate on

regular Haskell lists. The short of it is that it’s easy to do this;

recursion-schemes defines a data family called ‘Prim’ that basically endows

lists with base functor constructors of their own. You just need to use ‘Nil’

in place of ‘[]’ and ‘Cons’ in place of ‘(:)’.

Here’s insertion sort implemented in the same way, but for regular lists:

knockbackL :: Ord a => [a] -> [a]

knockbackL = apo coalg . project where

coalg Nil = Nil

coalg (Cons x l) = case project l of

Nil -> Cons x (Left l)

Cons h t

| x <= h -> Cons x (Left l)

| otherwise -> Cons h (Right (Cons x t))

insertionSortL :: Ord a => [a] -> [a]

insertionSortL = cata (knockbackL . embed)