27 Jun 2018

Take an iterated integral, e.g. \(\int_X \int_Y f(x, y) dy dx\). Fubini’s

Theorem describes the conditions under which the order of integration can

be swapped on this kind of thing while leaving its value invariant. If

Fubini’s conditions are met, you can convert your integral into \(\int_Y \int_X

f(x, y) dx dy\) and be guaranteed to obtain the same result you would have

gotten by going the other way.

What are these conditions? Just that you can glue your individual measures

together as a product measure, and that \(f\) is integrable with respect to it.

I.e.,

\[\int_{X \times Y} | f(x, y) | d(x \times y) < \infty.\]

Say you have a Giry monad implementation kicking around and you

want to see how Fubini’s Theorem works in terms of applicative functors,

monads, continuations, and all that. It’s pretty easy. You could start with

my old measurable library that sits on GitHub and attracts curious stars

from time to time and cook up the following example:

import Control.Applicative ((<$>), (<*>))

import Measurable

dx :: Measure Int

dx = bernoulli 0.5

dy :: Measure Double

dy = beta 1 1

dprod :: Measure (Int, Double)

dprod = (,) <$> dx <*> dy

Note that ‘dprod’ is clearly a product measure (I’ve constructed it using the

Applicative instance for the Giry monad, so it must be a product

measure) and take a simple, obviously integrable function:

add :: (Int, Double) -> Double

add (m, x) = fromIntegral m + x

Since ‘dprod’ is a product measure, Fubini’s Theorem guarantees that the

following are equivalent:

i0 :: Double

i0 = integrate add dprod

i1 :: Double

i1 = integrate (\x -> integrate (curry add x) dy) dx

i2 :: Double

i2 = integrate (\y -> integrate (\x -> curry add x y) dx) dy

And indeed they are – you can verify them yourself if you don’t believe me (or

our boy Fubini).

For an example of a where interchanging the order of integration would be

impossible, we can construct some other measure:

dpair :: Measure (Int, Double)

dpair = do

x <- dx

y <- fmap (* fromIntegral x) dy

return (x, y)

It can be integrated as follows:

i3 :: Double

i3 = integrate (\x -> integrate (curry add x) (fmap (* fromIntegral x) dy)) dx

But notice how ‘dpair’ is constructed: it is strictly monadic, not

applicative, so the order of the expressions matters. Since ‘dpair’ can’t be

expressed as a product measure (i.e. by an applicative expression), Fubini says

that swapping the order of integration is a no-no.

Note that if you were to just look at the types of ‘dprod’ and ‘dpair’ – both

‘Measure (Int, Double)’ – you wouldn’t be able to tell immediately that one

represents a product measure while the other one does not. If being able to

tell these things apart statically is important to you (say, you want to

statically apply order-of-integration optimisations to integral expressions or

what have you), you need look no further than the free applicative

functor to help you out.

Fun fact: there is a well-known variant of Fubini’s Theorem, called Tonelli’s

Theorem, that was developed by another Italian guy at around the same time.

I’m not sure how early-20th century Italy became so strong in

order-of-integration research, exactly.

22 Jan 2018

You can recognize truth by its beauty and simplicity.

– Richard Feynman (attributed)

In one of his early emails on the Cryptography mailing list, Satoshi

claimed that the proof-of-work chain is a solution to the Byzantine Generals

Problem (BGP). He describes this via an example where a bunch of

generals – Byzantine ones, of course – collude to break a king’s wifi.

It’s interesting to look at this a little closer in the language of the

originally-stated BGP itself. One doesn’t need to be too formal to glean

useful intuition here.

What, more precisely, did Satoshi claim?

The Decentralized Timestamp Server

Satoshi’s problem is that of a decentralized timestamp server (DTS).

Namely, he posits that any number of nodes, following some protocol, can

together act as a timestamping server – producing some consistent ordering on

what we’ll consider to be abstract ‘blocks’.

The decentralized timestamp server reduces to an instance of the Byzantine

Generals Problem as follows. There are a bunch of nodes, who could each be

honest or dishonest. All honest nodes want to agree on some ordering – a

history – of blocks, and a small number of dishonest nodes should not easily

be able to compromise that history – say, by convincing the honest nodes to

adopt some alternate one of their choosing.

(N.b. it’s unimportant here to be concerned about the contents of blocks.

Since the decentralized timestamp server problem is only concerned about

block orderings, we don’t need to consider the case of invalid transactions

within blocks or what have you, and can safely assume that any history must

be internally consistent. We only need to assume that child blocks depend

utterly on their parents, so that rewriting a history by altering some parent

block also necessitates rewriting its children, and that honest nodes are

constantly trying to append blocks.)

As demonstrated in the introduction to the original paper, the Byzantine

Generals Problem can be reduced to the problem of how any given node

communicates its information to others. In our context, it reduces to the

following:

Byzantine Generals Problem (DTS)

A node must broadcast a history of blocks to its peers, such that:

- (IC1) All honest peers agree on the history.

- (IC2) If the node is honest, then all honest peers agree with the history

it broadcasts.

To produce consensus, every node will communicate its history to others by

using a solution to the Byzantine Generals Problem.

Longest Proof-of-Work Chain

Satoshi’s proposed solution to the BGP has since come to be known as ‘Nakamoto

Consensus’. It is the following protocol:

Nakamoto Consensus

- Always use the longest history.

- Appending a block to any history requires a proof that a certain amount of

work – proportional in expectation to the total ‘capability’ of the

network – has been completed.

To examine how it works, consider an abstract network and communication medium.

We can assume that messages are communicated instantly (it suffices that

communication is dwarfed in time by actually producing a proof of work) and

that the network is static and fixed, so that only active or ‘live’ nodes

actually contribute to consensus.

The crux of Nakamoto consensus is that nodes must always use the longest

available history – the one that provably has the largest amount of work

invested in it – and appending to any history requires a nontrivial amount of

work in of itself. Consider a set of nodes, each having some (not necessarily

shared) history. Whenever any node broadcasts a one-block longer history,

all honest nodes will immediately agree on it, and conditions (IC1) and (IC2)

are thus automatically satisfied whether or not the broadcasting node is

honest. Nakamoto Consensus trivially solves the BGP in this most important

case; we can examine other cases by examining how they reduce to this one.

If two or more nodes broadcast longer histories at approximately the same time,

then honest nodes may not agree on a single history for as long as it takes a

longer history to be produced and broadcast. As soon as this occurs (which,

in all probability, is only a matter of time), we reduce to the previous case

in which all honest nodes agree with each other again, and the BGP is resolved.

The ‘bad’ outcome we’re primarily concerned about is that of dishonest nodes

rewriting history in their favour, i.e. by replacing some history \(\{\ldots,

B_1, B_2, B_3, \ldots\}\) by another one \(\{\ldots, B_1, B_2', B_3',

\ldots\}\) that somehow benefits them. The idea here is that some dishonest

node (or nodes) intends to use block \(B_2\) as some sort of commitment, but

later wants to renege. To do so, the node needs to rewrite not only \(B_2\),

but all other blocks that depend on \(B_2\) (here \(B_3\), etc.), ultimately

producing a longer history than is currently agreed upon by honest peers.

Moreover, it needs to do this faster than honest nodes are able to produce

longer histories on their own. Catching up to and exceeding the honest nodes

becomes exponentially unlikely in the number of blocks to be rewritten, and so

a measure of confidence can be ascribed to agreement on the state of any

sub-history that has been ‘buried’ by a certain number of blocks (see the

penultimate section of Satoshi’s paper for details).

Dishonest nodes that seek to replace some well-established, agreed-upon history

with another will thus find it effectively impossible (i.e. the probability is

negligible) unless they control a majority of the network’s capability – at

which point they no longer constitute a small number of peers.

Summary

So in the language of the originally-stated BGP: Satoshi claimed that the

decentralized timestamp server is an instance of the Byzantine Generals

Problem, and that Nakamoto Consensus (as it came to be known) is a solution to

the Byzantine Generals Problem. Because Nakamoto Consensus solves the BGP,

honest nodes that always use the longest proof-of-work history in the

decentralized timestamp network will eventually come to consensus on the

ordering of blocks.

01 Mar 2017

Last week Dan Peebles asked me on Twitter if I knew of any writing on the use

of recursion schemes for expressing stochastic processes or other probability

distributions. And I don’t! So I’ll write some of what I do know myself.

There are a number of popular statistical models or stochastic processes that

have an overtly recursive structure, and when one has some recursive structure

lying around, the elegant way to represent it is by way of a recursion scheme.

In the case of stochastic processes, this typically boils down to using an

anamorphism to drive things. Or, if you actually want to be able to observe

the thing (note: you do), an apomorphism.

By representing a stochastic process in this way one can really isolate the

probabilistic phenomena involved in it. One bundles up the essence of a

process in a coalgebra, and then drives it via some appropriate recursion

scheme.

Let’s take a look at three stochastic processes and examine their probabilistic

and recursive structures.

Foundations

To start, I’m going to construct a simple embedded language in the spirit of

the ones used in my simple probabilistic programming and comonadic

inference posts. Check those posts out if this stuff looks too

unfamiliar. Here’s a preamble that constitutes the skeleton of the code we’ll

be working with.

{-# LANGUAGE DeriveFunctor #-}

{-# LANGUAGE FlexibleContexts #-}

{-# LANGUAGE LambdaCase #-}

{-# LANGUAGE RankNTypes #-}

{-# LANGUAGE TypeFamilies #-}

import Control.Monad

import Control.Monad.Free

import qualified Control.Monad.Trans.Free as TF

import Data.Functor.Foldable

import Data.Random (RVar, sample)

import qualified Data.Random.Distribution.Bernoulli as RF

import qualified Data.Random.Distribution.Beta as RF

import qualified Data.Random.Distribution.Normal as RF

-- probabilistic instruction set, program definitions

data ModelF a r =

BernoulliF Double (Bool -> r)

| GaussianF Double Double (Double -> r)

| BetaF Double Double (Double -> r)

| DiracF a

deriving Functor

type Program a = Free (ModelF a)

type Model b = forall a. Program a b

type Terminating a = Program a a

-- core language terms

bernoulli :: Double -> Model Bool

bernoulli p = liftF (BernoulliF vp id) where

vp

| p < 0 = 0

| p > 1 = 1

| otherwise = p

gaussian :: Double -> Double -> Model Double

gaussian m s

| s <= 0 = error "gaussian: variance out of bounds"

| otherwise = liftF (GaussianF m s id)

beta :: Double -> Double -> Model Double

beta a b

| a <= 0 || b <= 0 = error "beta: parameter out of bounds"

| otherwise = liftF (BetaF a b id)

dirac :: a -> Program a b

dirac x = liftF (DiracF x)

-- interpreter

rvar :: Program a a -> RVar a

rvar = iterM $ \case

BernoulliF p f -> RF.bernoulli p >>= f

GaussianF m s f -> RF.normal m s >>= f

BetaF a b f -> RF.beta a b >>= f

DiracF x -> return x

-- utilities

free :: Functor f => Fix f -> Free f a

free = cata Free

affine :: Num a => a -> a -> a -> a

affine translation scale = (+ translation) . (* scale)

Just as a quick review, we’ve got:

- A probabilistic instruction set defined by ‘ModelF’. Each constructor

represents a foundational probability distribution that we can use in our

embedded programs.

- Three types corresponding to probabilistic programs. The ‘Program’ type

simply wraps our instruction set up in a naïve free monad. The ‘Model’

type denotes probabilistic programs that may not necessarily

terminate (in some weak sense), while the ‘Terminating’ type denotes

probabilistic programs that terminate (ditto).

- A bunch of embedded language terms. These are just probability

distributions; here we’ll manage with the Bernouli, Gaussian, and beta

distributions. We also have a ‘dirac’ term for constructing a Dirac

distribution at a point.

- A single interpeter ‘rvar’ that interprets a probabilistic program into a

random variable (where the ‘RVar’ type is provided by random-fu).

Typically I use mwc-probability for this but random-fu is quite

nice. When a program has been interpreted into a random variable we can use

‘sample’ to sample from it.

So: we can write simple probabilistic programs in standard monadic fashion,

like so:

betaBernoulli :: Double -> Double -> Model Bool

betaBernoulli a b = do

p <- beta a b

bernoulli p

and then interpret them as needed:

> replicateM 10 (sample (rvar (betaBernoulli 1 8)))

[False,False,False,False,False,False,False,True,True,False]

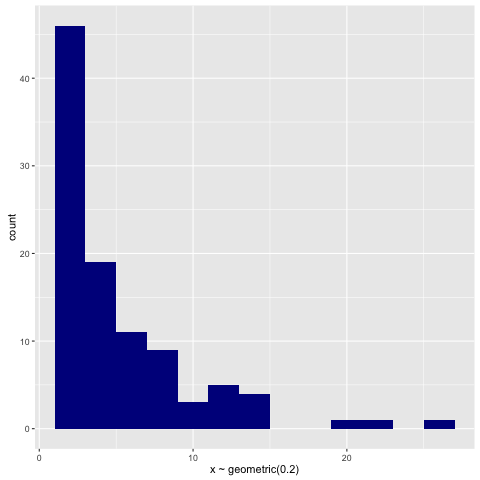

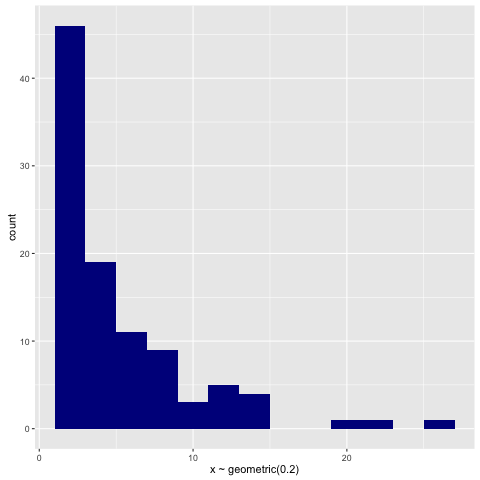

The Geometric Distribution

The geometric distribution is not a stochastic process per se, but it

can be represented by one. If we repeatedly flip a coin and then count the

number of flips until the first head, and then consider the probability

distribution over that count, voilà. That’s the geometric distribution. You

might see a head right away, or you might be infinitely unlucky and never see

a head. So the distribution is supported over the entirety of the natural

numbers.

For illustration, we can encode the coin flipping process in a straightforward

recursive manner:

simpleGeometric :: Double -> Terminating Int

simpleGeometric p = loop 1 where

loop n = do

accept <- bernoulli p

if accept

then dirac n

else loop (n + 1)

We start flipping Bernoulli-distributed coins, and if we observe a head we stop

and return the number of coins flipped thus far. Otherwise we keep flipping.

The underlying probabilistic phenomena here are the Bernoulli draw, which

determines if we’ll terminate, and the dependent Dirac return, which will wrap

a terminating value in a point mass. The recursive procedure itself has the

pattern of:

- If some condition is met, abort the recursion and return a value.

- Otherwise, keep recursing.

This pattern describes an apomorphism, and the recursion-schemes type

signature of ‘apo’ is:

apo :: Corecursive t => (a -> Base t (Either t a)) -> a -> t

It takes a coalgebra that returns an ‘Either’ value wrapped up in a base

functor, and uses that coalgebra to drive the recursion. A ‘Left’-returned

value halts the recursion, while a ‘Right’-returned value keeps it going.

Don’t be put off by the type of the coalgebra if you’re unfamiliar with

apomorphisms - its bark is worse than its bite. Check out my older post on

apomorphisms for a brief introduction to them.

With reference to the ‘apo’ type signature, The main thing to choose here is

the recursive type that we’ll use to wrap up the ‘ModelF’ base functor.

‘Fix’ might be conceivably simpler to start, so I’ll begin with that. The

coalgebra defining the model looks like this:

geoCoalg p n = BernoulliF p (\accept ->

if accept

then Left (Fix (DiracF n))

else Right (n + 1))

Then given the coalgebra, we can just wrap it up in ‘apo’ to represent the

geometric distribution.

geometric :: Double -> Terminating Int

geometric p = free (apo (geoCoalg p) 1)

Since the geometric distribution (weakly) terminates, the program has return

type ‘Terminating Int’.

Since we’ve encoded the coalgebra using ‘Fix’, we have to explicitly convert

to ‘Free’ via the ‘free’ utility function I defined in the preamble. Recent

versions of recursion-schemes have added a ‘Corecursive’ instance for ‘Free’,

though, so the superior alternative is to just use that:

geometric :: Double -> Terminating Int

geometric p = apo coalg 1 where

coalg n = TF.Free (BernoulliF p (\accept ->

if accept

then Left (dirac n)

else Right (n + 1)))

The point of all this is that we can isolate the core probabilistic phenomena

of the recursive process by factoring it out into a coalgebra. The recursion

itself takes the form of an apomorphism, which knows nothing about probability

or flipping coins or what have you - it just knows how to recurse, or stop.

For illustration, here’s a histogram of samples drawn from the geometric via:

> replicateM 100 (sample (rvar (geometric 0.2)))

An Autoregressive Process

Autoregressive (AR) processes simply use a previous epoch’s output as the

current epoch’s input; the number of previous epochs used as input on any given

epoch is called the order of the process. An AR(1) process looks like this,

for example:

\[y_t = \alpha + \beta y_{t - 1} + \epsilon_t\]

Here \(\epsilon_t\) are independent and identically-distributed random

variables that follow some error distribution. In other words, in this model

the value \(\alpha + \beta y_{t - 1}\) follows some probability distribution

given the last epoch’s output \(y_{t - 1}\) and some parameters \(\alpha\) and

\(\beta\).

An autoregressive process doesn’t have any notion of termination built into it,

so the purest way to represent one is via an anamorphism. We’ll focus on AR(1)

processes in this example:

ar1 :: Double -> Double -> Double -> Double -> Model Double

ar1 a b s = ana coalg where

coalg x = TF.Free (GaussianF (affine a b x) s (affine a b))

Each epoch is just a Gaussian-distributed affine transformation of the previous

epochs’s output. But the problem with using an anamorphism here is that it will

just shoot off to infinity, recursing endlessly. This doesn’t do us a ton of

good if we want to actually observe the process, so if we want to do that

we’ll need to bake in our own conditions for termination. Again we’ll rely on

an apomorphism for this; we can just specify how many periods we want to

observe the process for, and stop recursing as soon as we exceed that.

There are two ways to do this. We can either get a view of the process at

\(n\) periods in the future, or we can get a view of the process over \(n\)

periods in the future. I’ll write both, for illustration. The coalgebra for

the first is simpler, and looks like:

arCoalg (n, x) = TF.Free (GaussianF (affine a b x) s (\y ->

if n <= 0

then Left (dirac x)

else Right (pred m, y)))

The coalgebra is saying:

- Given \(x\), let \(z\) have a Gaussian distribution with mean \(\alpha +

\beta x\) and standard deviation \(s\).

- If we’re on the last epoch, return \(x\) as a Dirac point mass.

- Otherwise, continue recursing with \(z\) as input to the next epoch.

Now, to observe the process over the next \(n\) periods we can just collect

the observations we’ve seen so far in a list. An implementation of the

process, apomorphism and all, looks like this:

ar :: Int -> Double -> Double -> Double -> Double -> Terminating [Double]

ar n a b s origin = apo coalg (n, [origin]) where

coalg (epochs, history@(x:_)) =

TF.Free (GaussianF (affine a b x) s (\y ->

if epochs <= 0

then Left (dirac (reverse history))

else Right (pred epochs, y:history)))

(Note that I’m deliberately not handling the error condition here so as to

focus on the essence of the coalgebra.)

We can generate some traces for it in the standard way. Here’s how we’d sample

a 100-long trace from an AR(1) process originating at 0 with \(\alpha = 0\),

\(\beta = 1\), and \(s = 1\):

> sample (rvar (ar 100 0 1 1 0))

and here’s a visualization of 10 of those traces:

The Stick-Breaking Process

The stick breaking process is one of any number of whimsical stochastic

processes used as prior distributions in nonparametric Bayesian models. The

idea here is that we want to take a stick and endlessly break it into smaller

and smaller pieces. Every time we break a stick, we recursively take the rest

of the stick and break it again, ad infinitum.

Again, if we wanted to represent this endless process very faithfully, we’d use

an anamorphism to drive it. But in practice we’re going to only want to break

a stick some finite number of times, so we’ll follow the same pattern as the AR

process and use an apomorphism to do that:

sbp :: Int -> Double -> Terminating [Double]

sbp n a = apo coalg (n, 1, []) where

coalg (epochs, stick, sticks) = TF.Free (BetaF 1 a (\p ->

if epochs <= 0

then Left (dirac (reverse (stick : sticks)))

else Right (pred epochs, (1 - p) * stick, (p * stick):sticks)))

The coalgebra that defines the process says the following:

- Let the location \(p\) of the break on the next (normalized) stick be

beta\((1, \alpha)\)-distributed.

- If we’re on the last epoch, return all the pieces of the stick that we broke

as a Dirac point mass.

- Otherwise, break the stick again and recurse.

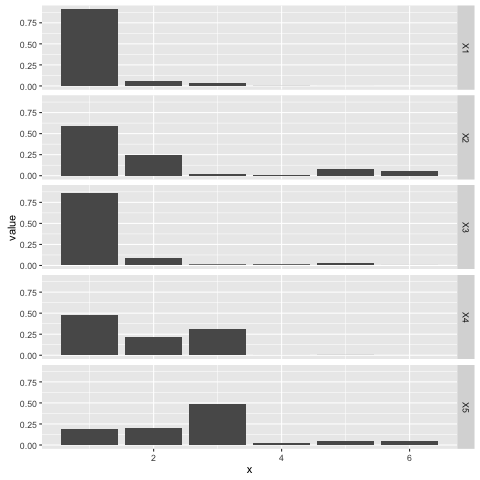

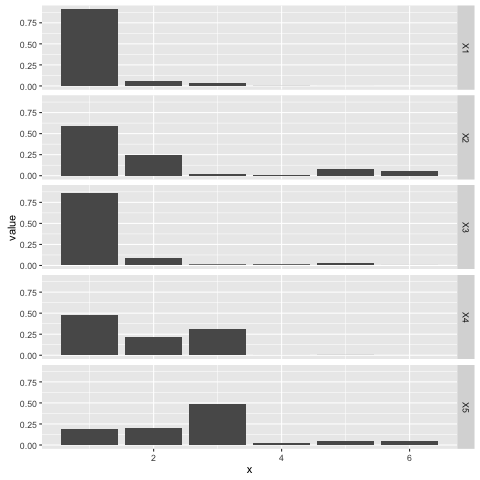

Here’s a plot of five separate draws from a stick breaking process with

\(\alpha = 0.2\), each one observed for five breaks. Note that each draw

encodes a categorical distribution over the set \(\{1, \ldots, 6\}\); the stick

breaking process is a ‘distribution over distributions’ in that sense:

The stick breaking process is useful for developing mixture models with an

unknown number of components, for example. The \(\alpha\) parameter can be

tweaked to concentrate or disperse probability mass as needed.

Conclusion

This seems like enough for now. I’d be interested in exploring other models

generated by recursive processes just to see how they can be encoded, exactly.

Basically all of Bayesian nonparametrics is based on using recursive processses

as prior distributions, so the Dirichlet process, Chinese Restaurant Process,

Indian Buffet Process, etc. should work beautifully in this setting.

Fun fact: back in 2011 before neural networks deep learning had taken over

machine learning, Bayesian nonparametrics was probably the hottest research

area in town. I used to joke that I’d create a new prior called the Malaysian

Takeaway Process for some esoteric nonparametric model and thus achieve machine

learning fame, but never did get around to that.

Addendum

I got a question about how I produce these plots. And the answer is the only

sane way when it comes to visualization in Haskell: dump the output to disk and

plot it with something else. I use R for most of my interactive/exploratory

data science-fiddling, as well as for visualization. Python with matplotlib is

obviously a good choice too.

Here’s how I made the autoregressive process plot, for example. First, I just

produced the actual samples in GHCi:

> samples <- replicateM 10 (sample (rvar (ar 100 0 1 1 0)))

Then I wrote them to disk:

> let render handle = hPutStrLn handle . filter (`notElem` "[]") . show

> withFile "trace.dat" WriteMode (\handle -> mapM_ (render handle) samples)

The following R script will then get you the plot:

require(ggplot2)

require(reshape2)

raw = read.csv('trace.dat', header = F)

d = data.frame(t(raw), x = seq_along(raw))

m = melt(d, id.vars = 'x')

ggplot(m, aes(x, value, colour = variable)) + geom_line()

I used ggplot2 for the other plots as well; check out the ggplot2

functions geom_histogram, geom_bar, and facet_grid in particular.