22 Sep 2024

I have a little library called sampling floating around for

general-purpose sampling from arbitrary foldable collections. It’s a

bit of a funny project: I originally hacked it together quickly, just

to get something done, so it’s not a very good library qua library –

it has plenty of unnecessary dependencies, and it’s not at all tuned

for performance. But it was always straightforward to use, and good

enough for my needs, so I’ve never felt any particular urge to update

it. Lately it caught my attention again, though, and I started thinking

about possible ways to revamp it, as well as giving it some much-needed

quality-of-life improvements, in order to make it more generally useful.

The library supports sampling with and without replacement in both the

equal and unequal-probability cases, from collections such as lists,

maps, vectors, etc. – again, anything with a Foldable instance.

In particular: the equal-probability, sampling-without-replacement

case depends on some code that Gabriella Gonzalez wrote for

reservoir sampling, a common online method for sampling from a

potentially-unbounded stream. I started looking into alternative

algorithms for reservoir sampling, to see what else was out there, and

discovered one that was extremely fast, extremely clever, and that

I’d never heard of before. It doesn’t seem to be that well-known, so I

simply want to illustrate it here, just so others are aware of it.

I learned about the algorithm from Erik Erlandson’s blog, but,

as he points out, it goes back almost forty years to one J.S

Vitter, who apparently also popularised the “basic” reservoir sampling

algorithm that everyone uses today (though it was not invented by him).

The basic reservoir sampling algorithm is simple. We’re sampling

some number of elements from a stream of unknown size: if we haven’t

collected enough elements yet, we just dump everything we see into our

“reservoir” (i.e., the collected sample); otherwise, we just generate a

random number and do a basic comparison to determine whether or not to

eject a value in our reservoir in favour of the new element we’ve just

seen. This is evidently also known as Algorithm R, and can apparently

be found in Knuth’s Art of Computer Programming. Here’s a basic

implementation that treats the reservoir as a mutable vector:

algo_r len stream prng = do

reservoir <- VM.new len

loop reservoir 0 stream

where

loop !sample index = \case

[] ->

V.freeze sample

(h:t)

| index < len -> do

VM.write sample index h

loop sample (succ index) t

| otherwise -> do

j <- S.uniformRM (0, index - 1) prng

when (j < len)

(VM.write sample j h)

loop sample (succ index) t

Here’s a quick, informal benchmark of it. Sampling 100 elements from a

stream of 10M 64-bit integers, using Marsaglia’s MWC256 PRNG,

yields the following runtime statistics on my mid-2020 MacBook Air:

73,116,027,160 bytes allocated in the heap

14,279,384 bytes copied during GC

45,960 bytes maximum residency (2 sample(s))

31,864 bytes maximum slop

6 MiB total memory in use (0 MiB lost due to fragmentation)

Tot time (elapsed) Avg pause Max pause

Gen 0 17639 colls, 0 par 0.084s 0.123s 0.0000s 0.0004s

Gen 1 2 colls, 0 par 0.000s 0.000s 0.0002s 0.0003s

INIT time 0.007s ( 0.006s elapsed)

MUT time 18.794s ( 18.651s elapsed)

GC time 0.084s ( 0.123s elapsed)

RP time 0.000s ( 0.000s elapsed)

PROF time 0.000s ( 0.000s elapsed)

EXIT time 0.000s ( 0.000s elapsed)

Total time 18.885s ( 18.781s elapsed)

%GC time 0.0% (0.0% elapsed)

Alloc rate 3,890,333,621 bytes per MUT second

Productivity 99.5% of total user, 99.3% of total elapsed

It’s fairly slow, and pretty much all we’re doing is generating 10M

random numbers.

In my experience, the most effective optimisations that can be made to

a numerical algorithm like this tend to be “mechanical” in nature –

avoiding allocation, cache misses, branch prediction failures,

etc. I find it exceptionally pleasing when there’s some domain-specific

intuition that admits substantial optimisation of an algorithm.

Vitter’s optimisation is along these lines. I find it as ingenious as

e.g. the kernel trick in the support vector machine context. The

crucial observation Vitter made is that one doesn’t need to consider

whether or not to add every single element he encounters to the

reservoir; the “gap” between entries also follows a well-defined

probability distribution, and one can just instead sample that in

order to determine the next element to add. Erik Erlandson points out

that when the size of the reservoir is small relative to the size of the

stream, as is typically the case, this distribution is well-approximated

by the geometric distribution – that which describes the number of coin

flips required before one observes a head (it has come up in a

couple of my previous blog posts).

So: the algorithm is adjusted so that, while processing the stream,

we sample how many elements to skip, and do so, then adding the next

element encountered after that to the reservoir. Here’s a version of

that, using Erlandson’s fast geometric approximation for sampling what

Vitter calls the skip distance:

data Loop =

Next

| Skip !Int

algo_r_optim len stream prng = do

reservoir <- VM.new len

go Next reservoir 0 stream

where

go what !sample !index = \case

[] ->

V.freeze sample

s@(h:t) -> case what of

Next

-- below the reservoir size, just write elements

| index < len -> do

VM.write sample index h

go Next sample (succ index) t

-- sample skip distance

| otherwise -> do

u <- S.uniformDouble01M prng

let p = fi len / fi index

skip = floor (log u / log (1 - p))

go (Skip skip) sample index s

Skip skip

-- stop skipping, use this element

| skip == 0 -> do

j <- S.uniformRM (0, len - 1) prng

VM.write sample j h

go Next sample (succ index) t

-- skip (d - 1) more elements

| otherwise ->

go (Skip (pred d)) sample (succ index) t

And now the same simple benchmark:

1,852,883,584 bytes allocated in the heap

210,440 bytes copied during GC

45,960 bytes maximum residency (2 sample(s))

31,864 bytes maximum slop

6 MiB total memory in use (0 MiB lost due to fragmentation)

Tot time (elapsed) Avg pause Max pause

Gen 0 445 colls, 0 par 0.002s 0.003s 0.0000s 0.0002s

Gen 1 2 colls, 0 par 0.000s 0.000s 0.0002s 0.0003s

INIT time 0.007s ( 0.007s elapsed)

MUT time 0.286s ( 0.283s elapsed)

GC time 0.002s ( 0.003s elapsed)

RP time 0.000s ( 0.000s elapsed)

PROF time 0.000s ( 0.000s elapsed)

EXIT time 0.000s ( 0.000s elapsed)

Total time 0.296s ( 0.293s elapsed)

%GC time 0.0% (0.0% elapsed)

Alloc rate 6,477,345,638 bytes per MUT second

Productivity 96.8% of total user, 96.4% of total elapsed

Both Vitter and Erlandson estimated orders of magnitude improvement

in sampling time, given we need to spend much less time iterating our

PRNG; here we see a 65x performance gain, with 40x less allocation.

Very impressive, and again, the optimisation is entirely probabilistic,

rather than “mechanical,” in nature (indeed, I haven’t tested any

mechanical optimisations to these implementations at all).

It turns out there are extensions in this spirit to unequal-probability

reservoir sampling as well, as is the method of “exponential jumps”

described in a 2006 paper by Efraimidis and Spirakis. I’ll

probably benchmark that algorithm too, and, if it fits the bill, and I

ever really do get around to properly updating my ‘sampling’ library,

I’ll refactor things to make use of these high-performance algorithms.

Let me know if you could use this sort of thing!

01 Sep 2024

Some years ago I wrote about using recursion schemes

to encode stochastic processes in an embedded probabilistic

programming setting. The crux of it was that recursion schemes

allow one to “factor out” the probabilistic phenomena from the recursive

structure of the process; the probabilistic stuff typically sits in

the so-called coalgebra of the recursion scheme, while the recursion

scheme itself dictates the manner in which the process evolves.

While it’s arguable as to whether this stuff is useful from a strictly

practical perspective (I would suggest “not”), I think the intuition one

gleans from it can be somewhat worthwhile, and my curious brain finds

itself wandering back to the topic from time to time.

I happened to take a look at this sort of framework again recently

and discovered that I couldn’t easily seem to implement a Chinese

Restaurant Process (CRP) – a stochastic process famous from the

setting of nonparametric Bayesian models – via either of the “standard”

patterns I used throughout my Recursive Stochastic Processes

post. This indicated that the recursive structure of the CRP differs

from the others I studied previously, at least in the manner I was

attempting to encode it in my particular embedded language setting.

So let’s take a look to see what the initial problem was, how one can

resolve it, and what insights we can take away from it all.

Framework

Here’s a simple and slightly more refined version of the embedded

probabilistic programming framework I introduced in some of my older

posts. I’ll elide incidental details, such as common imports and noisy

code that might distract from the main points.

First, some unfamiliar imports and minimal core types:

import qualified Control.Monad.Trans.Free as TF

import qualified System.Random.MWC.Probability as MWC

data ModelF r =

BernoulliF Double (Bool -> r)

| UniformF (Double -> r)

deriving Functor

type Model = Free ModelF

As a quick refresher, an expression of type ‘Model’ denotes a

probability distribution over some carrier type, and terms that

construct, manipulate, or interpret values of type ‘Model’ constitute

those of a simple embedded probabilistic programming language.

Importantly, here we’re using a very minimal such language, consisting

only of two primitives: the Bernoulli distribution (which is a

probability distribution over a coin flip) and the uniform distribution

over the interval [0, 1]. A trivial model that draws a probability of

success from a uniform distribution, and then flips a coin conditional

on that probability, would look like this, for example:

model :: Model Bool

model = Free (UniformF (\u ->

Free (BernoulliF pure))

(We could create helper functions such that programs in this embedded

language would be nicer to write, but that’s not the focus of this

post.)

We can construct expressions that denote stochastic processes by using

the normal salad of recursion schemes. Here’s how we can encode a

geometric distribution, for example, in which one counts the number of

coin flips required to observe a head:

geometric :: Double -> Model Int

geometric p = apo coalg 1 where

coalg n = TF.Free (BernoulliF p (\accept ->

if accept

then Left (pure n)

else Right (n + 1)))

The coalgebra isolates the probabilistic phenomena (a Bernoulli draw,

i.e. a coin flip), and the recursion scheme determines how the process

evolves (halting if a Bernoulli proposal is accepted). The coalgebra is

defined in terms of the so-called base or pattern functor of the

free monad type, defined in ‘Control.Monad.Trans.Free’ (see Practical

Recursion Schemes for a refresher on base functors if you’re

rusty).

The result is an expression in our embedded language, of course, and is

completely abstract. If we want to sample from the model it encodes, we

can use an interpreter like the following:

prob :: Model a -> MWC.Prob IO a

prob = iterM $ \case

BernoulliF p f -> MWC.bernoulli p >>= f

UniformF f -> MWC.uniform >>= f

where the ‘MWC’-prefixed functions are sampling functions from the

mwc-probability library, and ‘iterM’ is the familiar monadic

catamorphism-like recursion scheme over the free monad. This will

produce a function that can be sampled with ‘MWC.sample’ when provided

with a PRNG.

Here’s what some samples look like:

ghci> gen <- MWC.create

ghci> replicateM 10 (MWC.sample (prob (geometric 0.1)) gen)

[1,9,13,3,4,3,13,1,4,17]

Chinese Restaurant Process

The CRP is described technically as a stochastic process over “finite

integer partitions,” and, more memorably, over configurations of a

particular sort of indefinitely-large Chinese restaurant. One is to

imagine customers entering the restaurant sequentially; the first

sits at the first table available, and each additional customer is

either seated at a new table with probability proportional to some

dispersion parameter, or is seated at an occupied table with probability

proportional to the number of other customers already sitting there.

If each customer is labelled by how many others were in the restaurant

when they entered, the result is, for ‘n’ total customers, a random

partition of the natural numbers up to ‘n’. A particular realisation of

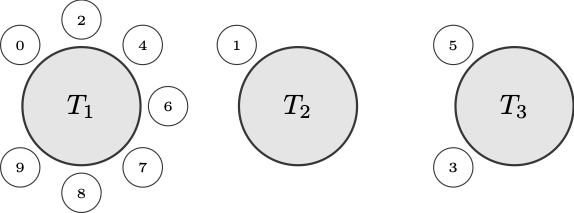

the process, following the arrival of 10 customers, might look like the

following:

[[9,8,7,6,4,2,0], [1], [5,3]]

This is a restaurant configuration after 10 arrivals, where each element

is a table populated by the labelled customers.

One of the rules of explaining the CRP is that you always have to

include a visualization like this:

It corresponds to the realised sample, and we certainly wouldn’t want to

break any pedagogical regulations.

Encoding, First Attempt

A natural way to encode the process is to seat each arriving customer at

a new table with the appropriate probability, and then, if it turns out

he is to be sat at an occupied table, to do that with the appropriate

conditional probability (i.e., conditional on the fact that he’s not

going to be seated at a new table).

So let’s imagine encoding a CRP with dispersion parameter ‘a’ and total

number of customers ‘n’. Our first attempt might go something like this:

crp n a = ana coalg (1, <initial restaurant>) where

coalg (customer, tables)

| customer >= n = TF.Pure tables

| otherwise =

let p = <probability of seating customer at new table>

in TF.Free (BernoulliF p (\accept ->

if accept

then (succ customer, <seat at new table>)

else ???

))

We run into a problem when we hit the ‘else’ branch of the conditional.

Here we want to express another random choice – viz., at which occupied

table do we seat the arriving customer. We’d want to do something like

‘TF.Free (UniformF (\u -> …))’ in that ‘else’ branch and then use the

produced uniform value to choose between the occupied tables based on

their conditional probabilities. But that will prove to be impossible,

given the type requirements.

There’s similarly no way to restructure things by producing the

desired uniform value earlier, before the conditional expression. For

appropriate type ‘t’, the coalgebra used for the anamorphism must have

type:

which in our case reduces to:

coalg :: a -> TF.FreeF ModelF a a

You’ll find that there’s simply no way to add another TF.Free

constructor to the mix while satisfying the above type. So it seems that

with an anamorphism (or apomorphism, which encounters the same problem)

we’re limited to denoting a single probabilistic operation on any

recursive call.

Encoding, Correctly

We thus need a recursion scheme that allows us to add multiple levels of

the base functor at a time. The most appropriate scheme appears to me

to be the futumorphism, which I also wrote about in Time Traveling

Recursion Schemes.

(As Patrick Thomson pointed out in his sublime series on

recursion schemes, both anamorphisms and apomorphisms are special cases

of the futumorphism.)

The coalgebra used by a futumorphism has a different type than that used

by an ana- or apomorphism, namely:

coalg :: a -> Base t (Free (Base t) a)

In our case, this is:

coalg :: a -> TF.FreeF ModelF a (Free (TF.FreeF ModelF a) a)

Note that here we’ll be able to use additional ‘TF.Free’ constructors

inside other expressions involving the base functor. In Time Traveling

Recursion Schemes I referred to this as “working with values that

don’t exist yet, while pretending like they do” – but better would

be to say that one is simply defining values to be produced during

(co)recursion, using separate monadic code.

Here’s how we’d encode the CRP using a futumorphism, in pseudocode:

crp n a = futu coalg (1, <initial restaurant>) where

coalg (customer, tables)

| customer >= n = TF.Pure tables

| otherwise =

let p = <probability of seating customer at new table>

in TF.Free (BernoulliF p (\accept ->

if accept

then pure (succ customer, <seat at new table>)

else do

res <- liftF (TF.Free (UniformF (\u ->

<seat amongst occupied tables using 'u'>

)))

pure (succ customer, res)))

Note that recursive points are expressed under a ‘TF.Free’ constructor

by returning a value (using ‘pure’) in the free monad itself. This

effectively allows us to use more than one embedded language construct

on each recursive call – as many as we want, as a matter of fact. The

familiar ‘liftF’ function lifts each such expression into the free

monad for us.

I mentioned in Time Traveling Recursion Schemes that this sort of

thing can look a little bit nicer if you have the appropriate embedded

language terms floating around. If we define the following:

uniform :: Free (TF.FreeF ModelF a) Double

uniform = liftF (TF.Free (UniformF id))

then we can use it to tidy things up a bit:

crp n a = futu coalg (1, <initial restaurant>) where

coalg (customer, tables)

| customer >= n = TF.Pure tables

| otherwise =

let p = <probability of seating customer at new table>

in TF.Free (BernoulliF p (\accept ->

if accept

then pure (succ customer, <seat at new table>)

else do

u <- uniform

let res = <seat amongst occupied tables using 'u'>

pure (succ customer, res)))

In any case, the futumorphism gets us to a faithfully-encoded CRP.

It allows us to express multiple probabilistic operations in every

recursive call, which is what’s required here due to our use of

conditional probabilities.

Alternative Encodings

Now. Recall that I mentioned the following:

A natural way to encode the process is to seat each arriving customer

at a new table with the appropriate probability, and then, if it

turns out he is to be sat at an occupied table, to do that with the

appropriate conditional probability (i.e., conditional on the fact

that he’s not going to be seated at a new table).

This is probably the most natural way to encode the process, and indeed,

if we only have Bernoulli and uniform language terms (or beta, Gaussian,

etc. in place of uniform – something that can at least be transformed

to produce a uniform, in any case), this seems to be the best we can do.

But it is not the only way to encode the CRP. If we have a language

term corresponding to a categorical distribution, then we can instead

choose between a new table and any of the occupied tables simultaneously

using the unconditional probabilities for each.

Let’s adjust our ModelF functor, adding a language term corresponding

to a categorical distribution. It will have as its parameter a list of

probabilities, one for each possible outcome under consideration:

data ModelF r =

BernoulliF Double (Bool -> r)

| UniformF (Double -> r)

| CategoricalF [Double] (Int -> r)

deriving Functor

With this we’ll be able to encode the CRP using a mere anamorphism, as

the following pseudocode describes:

crp n a = ana coalg (1, <initial restaurant>) where

coalg (customer, tables)

| customer >= n = TF.Pure tables

| otherwise =

let ps = <unconditional categorical probabilities>

in TF.Free (CategoricalF ps (\i ->

if i == 0

then (succ customer, <seat at new table>)

else (succ customer, <seat at occupied table 'i - 1'>)

))

Since here we only ever express a single probabilistic term during

recursion, the “standard” pattern we’ve used previously applies here.

But it’s worth noting that we could still employ the “unconditional,

then conditional” approach using a categorical distribution – we’d just

use the conditional probabilities to sample from the occupied tables

directly, rather than doing it in more low-level fashion using the

single uniform draw. Given an appropriate ‘categorical’ term, that would

look more like:

crp n a = futu coalg (1, <initial restaurant>) where

coalg (customer, tables)

| customer >= n = TF.Pure tables

| otherwise =

let p = <probability of seating customer at new table>

in TF.Free (BernoulliF p (\accept ->

if accept

then pure (succ customer, <seat at new table>)

else do

let ps = <conditional categorical probabilities>

i <- categorical ps

pure (succ customer, <seat at occupied table 'i'>)))

The recursive structure in this case is more complicated, requiring a

futumorphism instead of an anamorphism, but typically the conditional

probabilities are easier to compute.

Fin

So, some takeaways here, if one wants to indulge in this sort of

framework:

If we want to express a stochastic process using multiple probabilistic

operations in any given recursive call, we may need to employ a

scheme that supports richer (co)recursion than a plain anamorphism

or apomorphism. Here that’s captured nicely by a futumorphism, which

naturally captures what we’re looking for.

The same might be true if our functor is sufficiently limited, as

was the case here if we supported only the Bernoulli and uniform

distributions. There we had no option but to express the recursion using

condiitonal probabilistic operations, and so needed the richer recursive

structure that a futumorphism provides.

On the other hand, it may not be the case that one needs the richer

structure provided by a futumorphism, if instead one can express the

coalgebra using only a single layer of the base functor. Adding a

primitive categorical distribution to our embedded language eliminated

the need to use conditional probabilities when describing the recursion,

allowing us to drop back to a “basic” anamorphism.

Here is a gist containing a fleshed-out version of the code

above, if you’d like to play with it. Enjoy!

25 Feb 2020

Long ago, in the distant past, Curtis introduced the idea of kelvin

versioning in an informal blog post about Urbit. Imagining

the idea of an ancient and long-frozen form of Martian computing, he described

this versioning scheme as follows:

Some standards are extensible or versionable, but some are not. ASCII, for

instance, is perma-frozen. So is IPv4 (its relationship to IPv6 is little

more than nominal - if they were really the same protocol, they’d have the

same ethertype). Moreover, many standards render themselves incompatible in

practice through excessive enthusiasm for extensibility. They may not be

perma-frozen, but they probably should be.

The true, Martian way to perma-freeze a system is what I call Kelvin

versioning. In Kelvin versioning, releases count down by integer degrees

Kelvin. At absolute zero, the system can no longer be changed. At 1K, one

more modification is possible. And so on. For instance, Nock is at 9K. It

might change, though it probably won’t. Nouns themselves are at 0K - it is

impossible to imagine changing anything about those three sentences.

Understood in this way, kelvin versioning is very simple. One simply counts

downwards, and at absolute zero (i.e. 0K) no other releases are legal. It is

no more than a versioning scheme designed for abstract components that should

eventually freeze.

Many years later, the Urbit blog described kelvin versioning once more in the

post Towards a Frozen Operating System. This presented a significant

refinement of the original scheme, introducing both recursive and so-called

“telescoping” mechanics to it:

The right way for this trunk to approach absolute zero is to “telescope” its

Kelvin versions. The rules of telescoping are simple:

If tool B sits on platform A, either both A and B must be at absolute zero,

or B must be warmer than A.

Whenever the temperature of A (the platform) declines, the temperature of B

(the tool) must also decline.

B must state the version of A it was developed against. A, when loading B,

must state its own current version, and the warmest version of itself with

which it’s backward-compatible.

Of course, if B itself is a platform on which some higher-level tool C

depends, it must follow the same constraints recursively.

This is more or less a complete characterisation of kelvin versioning, but it’s

still not quite precise enough. If one looks at other versioning schemes that

try to communicate some specific semantic content (the most obvious example

being semver), it’s obvious that they take great pains to be formal and

precise about their mechanics.

Experience has demonstrated to me that such formality is necessary. Even the

excerpt above has proven to be ambiguous or underspecified re: the details of

various situations or corner cases that one might run into. These confusions

can be resolved by a rigorous protocol specification, which, in this case isn’t

very difficult to put together.

Kelvin versioning and its use in Urbit is the subject of the currently-evolving

UP9, recent proposed updates to which have not yet been ratified. The

following is my own personal take on and simple formal specification of kelvin

versioning – I believe it resolves any major ambiguities that the original

descriptions may have introduced.

Kelvin Versioning (Specification)

(The key words “MUST”, “MUST NOT”, “REQUIRED”, “SHALL”, “SHALL NOT”, “SHOULD”,

“SHOULD NOT”, “RECOMMENDED”, “MAY”, and “OPTIONAL” in this document are to be

interpreted as described in RFC 2119.)

For any component A following kelvin versioning,

-

A’s version SHALL be a nonnegative integer.

-

A, at any specific version, MUST NOT be modified after release.

-

At version 0, new versions of A MUST NOT be released.

-

New releases of A MUST be assigned a new version, and this version

MUST be strictly less than the previous one.

-

If A supports another component B that also follows kelvin versioning, then:

- Either both A and B MUST be at version 0, or B’s version MUST be

strictly greater than A’s version.

- If a new version of A is released and that version supports B, then a new

version of B MUST be released.

These rules apply recursively for any kelvin-versioned component C that is

supported by B, and so on.

Examples

Examples are particularly useful here, so let me go through a few.

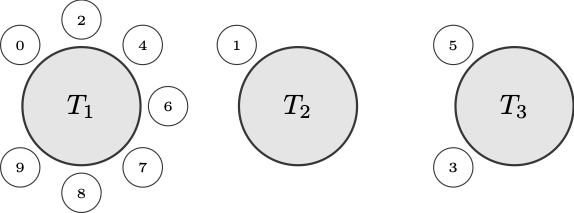

Let’s take the following four components, sitting in three layers, as a running

example. Here’s our initial state:

So we have A at 10K supporting B at 20K. B in turn supports both C at 21K and

D at 30K.

State 1

Imagine we have some patches lying around for D and want to release a new

version of it. That’s easy to do; we push out a new version of D. In this

case it will have version one less than 30, i.e. 29K:

A 10K

B 20K

C 21K

D 29K <-- cools from 30K to 29K

Easy peasy. This is the most trivial example.

The only possible point of confusion here is: well, what kind of change

warrants a version decrement? And the answer is: any (released) change

whatsoever. Anything with an associated kelvin version is immutable after

being released at that version, analogous to how things are done in any other

versioning scheme.

State 2

For a second example, imagine that we now have completed a major refactoring

of A and want to release a new version of that.

Since A supports B, releasing a new version of A obligates us to release a new

version of B as well. And since B supports both C and D, we are obligated,

recursively, to release new versions of those to boot.

The total effect of a new A release is thus the following:

A 9K <-- cools from 10K to 9K

B 19K <-- cools from 20K to 19K

C 20K <-- cools from 21K to 20K

D 28K <-- cools from 29K to 28K

This demonstrates the recursive mechanic of kelvin versioning.

An interesting effect of the above mechanic, as described in Toward a Frozen

Operating System is that anything that depends on (say) A, B, and C only

needs to express its dependency on some version of C. Depending on C at e.g.

20K implicitly specifies a dependency on its supporting component, B, at 19K,

and then A at 9K as well (since any change to A or B must also result in a

change to C).

State 3

Now imagine that someone has contributed a performance enhancement to C, and

we’d like to release a new version of that.

The interesting thing here is that we’re prohibited from releasing a new

version of C. Recall our current state:

A 9K

B 19K

C 20K <-- one degree K warmer than B

D 28K

Releasing a new version of C would require us to cool it by at least one

kelvin, resulting in the warmest possible version of 19K. But since its

supporting component, B, is already at 19K, this would constitute an illegal

state under kelvin versioning. A supporting component must always be strictly

cooler than anything it supports, or be at absolute zero conjointly with

anything it supports.

This illustrates the so-called telescoping mechanic of kelvin versioning – one

is to imagine one of those handheld telescopes made of segments that flatten

into each other when collapsed.

State 4

But now, say that we’re finally going to release our new API for B. We release

a new version of B, this one at 18K, which obligates us to in turn release new

versions of C and D:

A 9K

B 18K <-- cools from 19K to 18K

C 19K <-- cools from 20K to 19K

D 27K <-- cools from 28K to 27K

In particular, the new version of B gives us the necessary space to release a

new version of C, and, indeed, obligates us to release a new version of it. In

releasing C at 19K, presumably we’d include the performance enhancement that we

were prohibited from releasing in State 3.

State 5

A final example that’s simple, but useful to illustrate explicitly, involves

introducing a new component, or replacing a component entirely.

For example: say that we’ve decided to deprecate C and D and replace them with

a single new component, E, supported by B. This is as easy as it sounds:

A 9K

B 18K

E 40K <-- initial release at 40K

We just swap in E at the desired initial kelvin version. The initial kelvin

can be chosen arbitrarily; the only restriction is that it be warmer than the

the component that supports it (or be at absolute zero conjointly with it).

It’s important to remember that, in this component-resolution of kelvin

versioning, there is no notion of the “total temperature” of the stack. Some

third party could write another component, F, supported by E, with initial

version at 1000K, for example. It doesn’t introduce any extra burden or

responsibility on the maintainers of components A through E.

Collective Kelvin Versioning

So – all that is well and good for what I’ll call the component-level

mechanics of kelvin versioning. But it’s useful to touch on a related

construct, that of collectively versioning a stack of kelvin-versioned

components. This minor innovation on Curtis’s original idea was put together

by myself and my colleague Philip Monk.

If you have a collection of kelvin-versioned things, e.g. the things in our

initial state from the prior examples:

then you may want to release all these things, together, as some abstract

thing. Notably, this happens in the case of the Urbit kernel, where the stack

consists of a functional VM, an unapologetically amathematical purely

functional programming language, special-purpose kernel modules, etc.

It’s useful to be able to describe the whole kernel with a single version

number.

To do this in a consistent way, you can select one component in your stack to

serve as a primary index of sorts, and then capture everything it supports via

a patch-like, monotonically decreasing “fractional temperature” suffix.

This is best illustrated via example. If we choose B as our primary index in

the initial state above, for example, we could version the stack collectively

as 20.9K. B provides the 20K, and everything it supports is just lumped into

the “patch version” 9.

If we then consider the example given in State 1, i.e.:

in which D has cooled by a degree kelvin, then we can version this stack

collectively as 20.8K. If we were to then release a new version of C at 20K,

then we could release the stack collectively as 20.7K. And so on.

There is no strictly prescribed schedule as to how to decrease the fractional

temperature, but the following schedule is recommended:

.9, .8, .7, .., .1, .01, .001, .0001, ..

Similarly, the fractional temperature should reset to .9 whenever the primary

index cools. If we consider the State 2, for example, where a new release of A

led to every other component in the stack cooling, we had this:

Note that B has cooled by a kelvin, so we would version this stack collectively

as 19.9K. The primary index has decreased by a kelvin, and the fractional

temperature has been reset to .9.

While I think examples illustrate this collective scheme most clearly, after my

schpeel about the pitfalls of ambiguity it would be remiss of me not to include

a more formal spec:

Collective Kelvin Versioning (Specification)

(The key words “MUST”, “MUST NOT”, “REQUIRED”, “SHALL”, “SHALL NOT”, “SHOULD”,

“SHOULD NOT”, “RECOMMENDED”, “MAY”, and “OPTIONAL” in this document are to be

interpreted as described in RFC 2119.)

For a collection of kelvin-versioned components K:

-

K’s version SHALL be characterised by a primary index, chosen from a

component in K, and and a real number in the interval [0, 1) (the

“fractional temperature”), determined by all components that the primary

index component supports.

The fractional temperature MAY be 0 only if the primary index’s version

is 0.

-

K, at any particular version, MUST NOT be modified after release.

-

At primary index version 0 and fractional temperature 0, new versions of K

MUST NOT be released.

-

New releases of K MUST be assigned a new version, and this version

MUST be strictly less than the previous one.

-

When a new release of K includes new versions of any component supported by

the primary index, but not a new version of the primary index proper, its

fractional temperature MUST be less than the previous version.

Given constant primary index versions, fractional temperatures corresponding

to new releases SHOULD decrease according to the following schedule:

.9, .8, .7, .., .1, .01, .001, .0001, ..

-

When a new release of K includes a new version of the primary index, the

fractional temperature of SHOULD be reset to 9.

-

New versions of K MAY be indexed by components other than the primary

index (i.e., K may be “reindexed” at any point). However, the new chosen

component MUST either be colder than the primary index it replaces, or

be at version 0 conjointly with the primary index it replaces.

Etc.

In my experience, the major concern in adopting a kelvin versioning scheme is

that one will accidentally initialise everything with a set of temperatures

(i.e. versions) that are too cold (i.e. too close to 0), and thus burn through

too many version numbers too quickly on the path to freezing. To alleviate

this, it helps to remember that one has an infinite number of release

candidates available for every component at every temperature.

The convention around release candidates is just to prepend a suffix to the

next release version along the lines of .rc1, .rc2, etc. One should feel

comfortable using these liberally, iterating through release candidates as

necessary before finally committing to a new version at a properly cooler

temperature.

The applications that might want to adopt kelvin versioning are probably pretty

limited, and may indeed even be restricted to the Urbit kernel itself (Urbit

has been described by some as “that operating system with kernel that

eventually reaches absolute zero under kelvin versioning”). Nonetheless: I

believe this scheme to certainly be more than a mere marketing gimmick or what

have you, and, at minimum, it makes for an interesting change of pace from

semver.